Crisis management and COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic is a historic milestone at many levels and has launched the world into crisis management mode—all individuals and organizations have had the urgent need to manage this crisis in one way or another. A crisis does indeed bring many threats, but it can also bring opportunities. Research and practice show different phases in the crisis management process, including a need for action at different levels and that information is a central resource.

Crisis Management Before, During, and After

Experiencing a crisis and the necessary management of the crisis are not new to the world. Many crises happened in the past and more will indeed occur in the future. Crises can involve our health and welfare or our financial situation; it can be an environmental or natural disaster. Crises can result from technological issues, terrorist attacks, or even infrastructure destruction (Pearson and Mitroff, 1993). Sadly, in our most recent past, the United States (and the world) endured the September 11th, 2001 terrorist attacks in three states, including in New York City, where citizens witnessed the destruction of the twin towers of the World Trade Center, and where the overall day resulted in thousands of Americans’ lives lost (Brouard, 2004b). There was the attack to the office of the French satirical weekly newspaper, Charlie Hebdo, in Paris on January 2015 (Lançon, 2018); the devastating fire at Notre-Dame de Paris in April 2019; or the ice storm in parts of Ontario and Quebec in January 1998—a storm considered among the worst natural disasters in Canadian history. These are examples of times where the world had to switch into crisis-management mode and navigate through the tragic circumstances. And, it is amid the current COVID-19 pandemic that we recognize the importance of a carefully thought-out plan that deploys the strategies required to deal effectively with this crisis and come through the other side with minimal side effects.

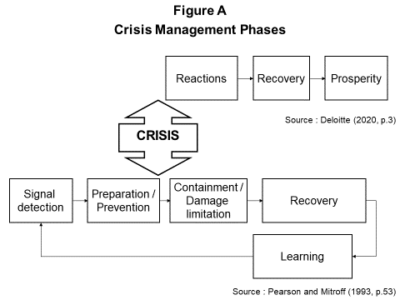

Figure A summarizes two visions of the various phases in crisis management. Each outlines the before (signal detection, preparation, prevention), during (reactions, containment, damage limitation), and after (recovery, prosperity, learning) a crisis. The first pathway focuses more on during and after the crisis, while the second pathway takes a more global perspective. In our view, it is preferable to adopt a more proactive approach, which also includes the actions following the crisis, instead of just a reactive approach.

Organizational Disruption and Need for Action

When a crisis hits our personal and professional lives, an immediate series of actions are required, both at the individual, as well as at the organizational levels. Moreover, there are numerous areas to consider, such as the human implications, the social aspects, the emotional elements, as well as the technological, financial, and economic impacts (Pearson and Mitroff, 1993). Organizational challenges include health of employees and customers, cash flows, business continuity, risk management, strategy, supply chain, and taxation (Deloitte Canada, 2020). Actions to solve immediate problems in any of the above-mentioned areas occupy a large portion of our current activities. For example, we could think of reorganizing our home to accommodate our ability to do our jobs, finding secondary options to replace sources of income, or the need to arrange an office space to ensure proper and adequate physical distancing. However, those actions (or reactions) should be seen (in part) in advance by capturing signals of a potential crisis to prevent or prepare for it. Strategic intelligence and foresight efforts are a good way to prepare for various changes in the macro-environment affecting stakeholders (Brouard, 2004a). Detecting signals and planning will help in facing the next crisis.

Information is Pivotal

As we see with the daily reports of health information on COVID-19 from many sources (for example, epidemiology updates, dashboards, mapping, projections, Ottawa Public Health, 2020), information is vital and necessary for decision making. Collection, analysis, and dissemination of this information is essential for various business decisions during all the crisis-management phases (Brouard, 2004a). This is demonstrated in many contexts, even beyond a crisis, where numerous information exchanges and reporting are present in complex ecosystems (see Brouard and Glass, 2017, for an example regarding grantmaking foundations).

All organizations (public, private, and nonprofits) should take the time to learn about the crisis that they are experiencing. This will help in structured planning efforts and ongoing updates. As well, lessons should be learned to prepare for the next crisis. After all, preparedness and knowledge are key to overcome adversity.

About the author: François Brouard, DBA, FCPA, FCA is a Full Professor (Accounting and Taxation), Sprott School of Business, Carleton University; founding Director of Sprott Centre for Social Enterprises/Centre Sprott pour les entreprises sociales (SCSE/CSES), and co-leader Professional Accounting Research Group (PARG).

REFERENCES

Brouard, F. (2004a). Développement d’un outil diagnostique des pratiques existantes de la veille stratégique auprès des PME [Development of a Diagnostic Tool on Environmental Scanning Practices in SME], thèse de doctorat/dissertation thesis, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, May. [Online]

Brouard, F. (2004b). Business Intelligence for Canadian Corporations After September 11. Journal of Competitive Intelligence and Management, 2(1), 1-15.

Brouard, F., Glass, J. (2017). Understanding Information Exchanges and Reporting by Grantmaking Foundations. ANSERJ – Revue canadienne de recherche sur les OSBL et l’économie sociale/Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Ressearch, 8(2), 40-56.

Deloitte Canada. (2020). COVID-19: Orchestrer la reprise des organisations et des chaînes d’approvisionnement. 24p. [Online] (5 avril 2020).

Lançon, P. (2018). Le lambeau, Paris: Éditions Gallimard.

Ottawa Public Health (2020). Statistics on Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). [Online] (7 June 2020).

Pearson, C.M., Mitroff, I.I. (1993). From Crisis Prone to Crisis Prepared: A Framework for Crisis Management. Academy of Management Executive, 7(1), 48-59.